Many custom options...

And formats...

No Fear in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a No Fear calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “No Fear” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “No Fear” title below...

1. No Fear

4. Preparation Yields No Fear or Worries

5. Fear No Evil

7. Confidence / Faithful Heart

8. The Confident Helmsman Inspires Confidence in the Passengers

10. Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks

11. Fear not long roads; Fear only short ambition

12. Do not fear being slow, fear standing still

13. Do not fear poverty; Fear low ambitions

14. No Mind / Mushin

15. Preparation Yields No Regrets

16. Never Give Up

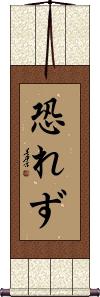

No Fear

恐れず is probably the best way to express “No Fear” in Japanese.

The first Kanji and the following Hiragana character create a word that means: to fear, to be afraid of, frightened, or terrified.

The last Hiragana character serves to modify and negate the first word (put it in negative form). Basically, they carry a meaning like “without” or “keeping away.” 恐れず is almost like the English modifier “-less.”

Altogether, you get something like “Without Fear” or “Fearless.”

Here's an example of using this in a sentence: 彼女かのじょは思い切ったことを恐れずにやる。

Translation: She is not scared of taking big risks.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

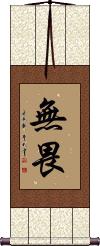

No Fear

(2 characters)

無畏 literally means “No Fear.” But perhaps not the most natural Chinese phrase (see our other “No Fear” phrase for a complete thought). However, this two-character version of “No Fear” seems to be a very popular way to translate this into Chinese when we checked Chinese Google.

Note: This also means “No Fear” in Japanese and Korean, but this character pair is not often used in Japan or Korea.

This term appears in various Chinese dictionaries with definitions like “without fear,” intrepidity, fearless, dauntless, and bold.

In the Buddhist context, this is a word derived from the word Abhaya, meaning: Fearless, dauntless, secure, nothing, and nobody to fear. Also, from vīra meaning: courageous, bold.

See Also: Never Give Up | No Worries | Undaunted | Bravery | Courage | Fear No Man

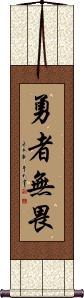

No Fear

(four-character version)

勇者無畏 is a complete sentence that means “Brave People Have No Fear” or “A Brave Person Has No Fear” (plural or singular is not implied).

We translated “No Fear” into the two variations that you will find on our website. Then we checked Chinese Google and found that others had translated “No Fear” in the exact same ways. Pick the one you like best. A great gift for your fearless friend.

See Also: Fear No Man

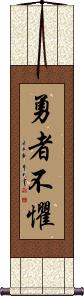

The Brave Have No Fears

This proverb means “Brave people [are] without fear,” or “The brave are without fear.”

勇者不懼 is a proverb credited to Confucius. It's one of three phrases in a set of things he said.

This phrase is originally Chinese but has penetrated Japanese culture as well (many Confucian phrases have) back when Japan borrowed Chinese characters into their language.

This phrase has also been converted into modern Japanese grammar when written as 勇者は懼れず. If you want this version just click on those characters.

See Also: No Fear

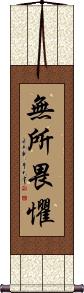

Fear No Man / Fear Nothing

無所畏懼 means “fear nothing,” but it's the closest thing in Chinese to the phrase “fear no man” which many of you have requested.

This would also be the way to say “fear nobody” and can be translated simply as “undaunted.”

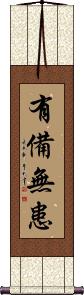

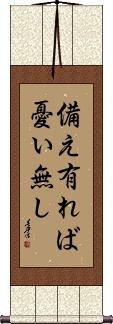

Preparation Yields No Fear or Worries

有備無患 means “When you are well-prepared, you have nothing to fear.”

Noting that the third character means “no” or “without” and modifies the last... The last character can mean misfortune, troubles, worries, or fears. It could even be stretched to mean sickness. Therefore you can translate this proverb in a few ways. I've also seen it translated as “Preparedness forestalls calamities.”

有備無患 is comparable to the English idiom, “Better safe than sorry,” but does not directly/literally mean this.

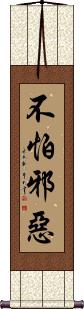

Fear No Evil

不怕邪惡 literally means “no fear of evil” in Chinese.

Chinese grammar and word order are a little different than English. 不怕邪惡 is the best way to write something that means “fear no evil” in Chinese.

The first character means “not,” “don't” or “no.”

The second means “fear.”

The last two mean “evil” but can also be translated as sinister, vicious, wickedness, or just “bad.”

Fear No Evil

悪を恐れない is “Fear No Evil” in Japanese.

Japanese grammar and phrase construction is different than English, so this literally reads, “Evil Fear Not.”

The “evil” Kanji can also be translated as “wickedness.”

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Fearless / Daring

大胆不敵 is a Japanese word that can mean a few things depending on how you read it.

Popular translations include fearless, audacity (the attitude of a) daredevil, or daring.

The first two Kanji create a word that means: bold, fearless, or daring; audacious.

The last two Kanji create a word meaning: no match for, cannot beat, daring, fearless, intrepid, bold, or tough.

As with many Japanese words, the two similar-meaning words work together to multiply the meaning and intensity of the whole 4-Kanji word.

Confidence / Faithful Heart

信心 is a Chinese, Japanese, and Korean word that means confidence, faith, or belief in somebody or something.

The first character means faith, and the second can mean heart or soul. Therefore, you could say this means “faithful heart” or “faithful soul.”

In Korean especially, this word has a religious connotation.

In the old Japanese Buddhist context, this was a word for citta-prasāda (clear or pure heart-mind).

In modern Japan (when read by non-Buddhists), this word is usually understood as “faith,” “belief,” or “devotion.”

See Also: Self-Confidence

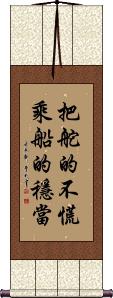

The Confident Helmsman Inspires Confidence in the Passengers

把舵的不慌乘船的稳当 is a Chinese proverb that literally translates as: [If the] helmsman is not nervous, the passengers [will feel] secure.

Figuratively, this means: If the leader appears confident, his/her followers will gain confidence also.

This is a great suggestion that a confident leader inspires confidence in his/her troops or followers. Of course, a nervous leader will create fear in troops or followers.

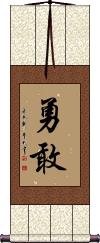

Bravery / Courage

Courage in the face of Fear

勇敢 is about courage or bravery in the face of fear.

You do the right thing even when it is hard or scary. When you are courageous, you don't give up. You try new things. You admit mistakes. This kind of courage is the willingness to take action in the face of danger and peril.

勇敢 can also be translated as braveness, valor, heroic, fearless, boldness, prowess, gallantry, audacity, daring, dauntless, and/or courage in Japanese, Chinese, and Korean. This version of bravery/courage can be an adjective or a noun. The first character means bravery and courage by itself. The second character means “daring” by itself. The second character emphasizes the meaning of the first but adds the idea that you are not afraid of taking a dare, and you are not afraid of danger.

勇敢 is more about brave behavior and not so much the mental state of being brave. You'd more likely use this to say, “He fought courageously in the battle,” rather than “He is very courageous.”

Undaunted After Repeated Setbacks

Persistence to overcome all challenges

百折不撓 is a Chinese proverb that means “Be undaunted in the face of repeated setbacks.”

More directly translated, it reads, “[Overcome] a hundred setbacks, without flinching.” 百折不撓 is of Chinese origin but is commonly used in Japanese and somewhat in Korean (same characters, different pronunciation).

This proverb comes from a long, and occasionally tragic story of a man that lived sometime around 25-220 AD. His name was Qiao Xuan, and he never stooped to flattery but remained an upright person at all times. He fought to expose the corruption of higher-level government officials at great risk to himself.

Then when he was at a higher level in the Imperial Court, bandits were regularly capturing hostages and demanding ransoms. But when his own son was captured, he was so focused on his duty to the Emperor and the common good that he sent a platoon of soldiers to raid the bandits' hideout, and stop them once and for all even at the risk of his own son's life. While all of the bandits were arrested in the raid, they killed Qiao Xuan's son at first sight of the raiding soldiers.

Near the end of his career, a new Emperor came to power, and Qiao Xuan reported to him that one of his ministers was bullying the people and extorting money from them. The new Emperor refused to listen to Qiao Xuan and even promoted the corrupt Minister. Qiao Xuan was so disgusted that in protest, he resigned from his post as minister (something almost never done) and left for his home village.

His tombstone reads “Bai Zhe Bu Nao” which is now a proverb used in Chinese culture to describe a person of strong will who puts up stubborn resistance against great odds.

My Chinese-English dictionary defines these 4 characters as “keep on fighting despite all setbacks,” “be undaunted by repeated setbacks,” and “be indomitable.”

Our translator says it can mean “never give up” in modern Chinese.

Although the first two characters are translated correctly as “repeated setbacks,” the literal meaning is “100 setbacks” or “a rope that breaks 100 times.” The last two characters can mean “do not yield” or “do not give up.”

Most Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people will not take this absolutely literal meaning but will instead understand it as the title suggests above. If you want a single big word definition, it would be indefatigability, indomitableness, persistence, or unyielding.

See Also: Tenacity | Fortitude | Strength | Perseverance | Persistence

Fear not long roads; Fear only short ambition

不怕路遠隻怕志短 is a Chinese proverb that literally translates as “Fear not long roads; fear only short ambition,” or “Don't fear that the road is long, only fear that your will/ambition/aspiration is short.”

Figuratively, this means: However difficult the goal is, one can achieve it as long as one is determined to do so.

Others may translate the meaning as “Don't let a lack of willpower stop you from pressing onward in your journey.”

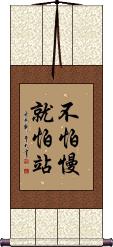

Do not fear being slow, fear standing still

Do not fear poverty; Fear low ambitions

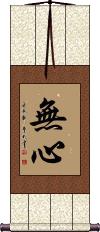

No Mind / Mushin

In Japanese, 無心 means innocent or without knowledge of good and evil. It literally means “without mind.”

無心 is one of the five spirits of the warrior (budo) and is often used as a Japanese martial arts tenet. Under that context, places such as the Budo Dojo define it this way: “No mind, a mind without ego. A mind like a mirror which reflects and dos not judge.” The original term was “mushin no shin,” meaning “mind of no mind.” It is a state of mind without fear, anger, or anxiety. Mushin is often described by the phrase “Mizu no Kokoro,” which means “mind like water.” The phrase is a metaphor describing the pond that clearly reflects its surroundings when calm but whose images are obscured once a pebble is dropped into its waters.

This has a good meaning in conjunction with Chan / Zen Buddhism in Japan. However, out of that context, it means mindlessness or absent-mindedness. To non-Buddhists in China, this is associated with doing something without thinking.

In Korean, this usually means indifference.

Use caution and know your audience before ordering this selection.

More info: Wikipedia: Mushin

Preparation Yields No Regrets

Never Give Up

The first character means “eternal” or “forever,” and the second means “not” (together, they mean “never”). The last two characters mean “give up” or “abandon.” Altogether, you can translate this proverb as “never give up” or “never abandon.”

Depending on how you want to read this, 永不放棄 is also a statement that you will never abandon your hopes, dreams, family, or friends.

Dana: Almsgiving and Generosity

布施 is the Buddhist practice of giving known as Dāna or दान from Pali and Sanskrit.

Depending on the context, this can be alms-giving, acts of charity, or offerings (usually money) to a priest for reading sutras or teachings.

Some will put Dāna in these two categories:

1. The pure or unsullied charity, which looks for no reward here but only in the hereafter.

2. The sullied almsgiving whose object is personal benefit.

The first kind is, of course, the kind that a liberated or enlightened person will pursue.

Others will put Dāna in these categories:

1. Worldly or material gifts.

2. Unworldly or spiritual gifts.

You can also separate Dāna into these three kinds:

1. 財布施 Goods such as money, food, or material items.

2. 法布施 Dharma, as an act to teach or bestow the Buddhist doctrine onto others.

3. 無畏布施 Courage, as an act of facing fear to save someone or when standing up for someone or standing up for righteousness.

The philosophies and categorization of Dāna will vary among various monks, temples, and sects of Buddhism.

Breaking down the characters separately:

布 (sometimes written 佈) means to spread out or announce, but also means cloth. In ancient times, cloth or robs were given to the Buddhist monks annually as a gift of alms - I need to do more research, but I believe there is a relationship here.

施 means to grant, to give, to bestow, to act, to carry out, and by itself can mean Dāna as a single character.

Dāna can also be expressed as 檀那 (pronounced “tán nà” in Mandarin and dan-na or だんな in Japanese). 檀那 is a transliteration of Dāna. However, it has colloquially come to mean some unsavory or unrelated things in Japanese. So, I think 布施 is better for calligraphy on your wall to remind you to practice Dāna daily (or whenever possible).

Fatal error: Cannot redeclare function foreignPrice() (previously declared in /home/gwest/web/chinesescrollpainting.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php:22) in /home/gwest/web/orientaloutpost.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php on line 22