Many custom options...

And formats...

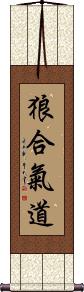

Wolf in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a Wolf calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “Wolf” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “Wolf” title below...

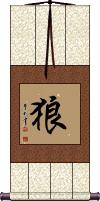

1. Wolf

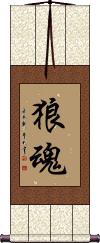

2. Wolf Spirit / Soul of a Wolf

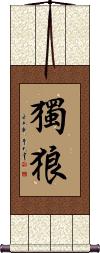

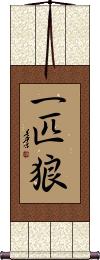

3. Lone Wolf

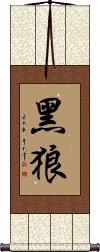

4. Black Wolf

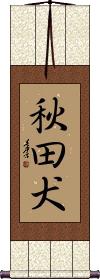

5. Akita Dog / Akitainu / Akita Inu

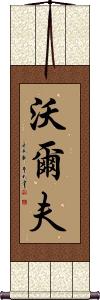

6. Randolph

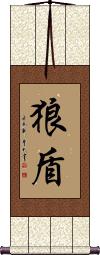

Wolf

狼 is the character used to represent the elusive animal known as the wolf in both Chinese and Japanese.

If you are a fan of the wolf or the wolf means something special to you, this could make a great addition to your wall.

Do keep in mind, that much like our perception of wolves in the history of western culture, eastern cultures do not have a very positive view of wolves (save the scientific community and animal lovers). The wolf is clearly an animal that is misunderstood or feared the world over.

狼 is seldom used alone in Korean Hanja but is used in a compound word that means utter failure (as in a wolf getting into your chicken pen - or an otherwise ferocious failure). Not a good choice if your audience is Korean.

Wolf

Wolf Spirit / Soul of a Wolf

Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf

Black Wolf

Akita Dog / Akitainu / Akita Inu

鞦田犬 is the Japanese title of the breed of dog known as an Akita.

Technically, the title above means “Akita hound” or “Akita Dog.” The literal translation of these characters is “autumn field dog.”

Note: This title is Japanese only. In China, this breed of dog is referred to as "The Japanese breed" (literally: Japanese hound).

Chinese title: ![]()

![]()

![]()

Randolph

Okami Hapkido

Better Late Than Never

It's Never Too Late Too Mend

Long ago in what is now China, there were many kingdoms throughout the land. This time period is known as “The Warring States Period” by historians because these kingdoms often did not get along with each other.

Sometime around 279 B.C. the Kingdom of Chu was a large but not particularly powerful kingdom. Part of the reason it lacked power was the fact that the King was surrounded by “yes men” who told him only what he wanted to hear. Many of the King's court officials were corrupt and incompetent which did not help the situation.

The King was not blameless himself, as he started spending much of his time being entertained by his many concubines.

One of the King's ministers, Zhuang Xin, saw problems on the horizon for the Kingdom, and warned the King, “Your Majesty, you are surrounded by people who tell you what you want to hear. They tell you things to make you happy and cause you to ignore important state affairs. If this is allowed to continue, the Kingdom of Chu will surely perish, and fall into ruins.”

This enraged the King who scolded Zhuang Xin for insulting the country and accused him of trying to create resentment among the people. Zhuang Xin explained, “I dare not curse the Kingdom of Chu but I feel that we face great danger in the future because of the current situation.” The King was simply not impressed with Zhuang Xin's words.

Seeing the King's displeasure with him and the King's fondness for his court of corrupt officials, Zhuang Xin asked permission from the King that he may take leave of the Kingdom of Chu, and travel to the State of Zhao to live. The King agreed, and Zhuang Xin left the Kingdom of Chu, perhaps forever.

Five months later, troops from the neighboring Kingdom of Qin invaded Chu, taking a huge tract of land. The King of Chu went into exile, and it appeared that soon, the Kingdom of Chu would no longer exist.

The King of Chu remembered the words of Zhuang Xin and sent some of his men to find him. Immediately, Zhuang Xin returned to meet the King. The first question asked by the King was “What can I do now?”

Zhuang Xin told the King this story:

A shepherd woke one morning to find a sheep missing. Looking at the pen saw a hole in the fence where a wolf had come through to steal one of his sheep. His friends told him that he had best fix the hole at once. But the Shepherd thought since the sheep is already gone, there is no use fixing the hole.

The next morning, another sheep was missing. And the Shepherd realized that he must mend the fence at once. Zhuang Xin then went on to make suggestions about what could be done to reclaim the land lost to the Kingdom of Qin, and reclaim the former glory and integrity of the Kingdom of Chu.

The Chinese idiom shown above came from this reply from Zhuang Xin to the King of Chu almost 2,300 years ago.

It translates roughly into English as...

“Even if you have lost some sheep, it's never too late to mend the fence.”

This proverb, 亡羊补牢犹未为晚, is often used in modern China when suggesting in a hopeful way that someone change their ways, or fix something in their life. It might be used to suggest fixing a marriage, quitting smoking, or getting back on track after taking an unfortunate path in life among other things one might fix in their life.

I suppose in the same way that we might say, “Today is the first day of the rest of your life” in our western cultures to suggest that you can always start anew.

Note: This does have Korean pronunciation but is not a well-known proverb in Korean (only Koreans familiar with ancient Chinese history would know it). Best if your audience is Chinese.

Fatal error: Cannot redeclare foreignPrice() (previously declared in /home/gwest/web/chinesescrollpainting.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php:22) in /home/gwest/web/orientaloutpost.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php on line 22