Many custom options...

And formats...

Not what you want?

Try other similar-meaning words, fewer words, or just one word.

Wisdom Intelligence in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a Wisdom Intelligence calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “Wisdom Intelligence” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “Wisdom Intelligence” title below...

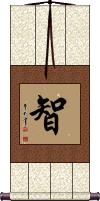

Wisdom

智 is the simplest way to write wisdom in Chinese, Korean Hanja, and Japanese Kanji.

Being a single character, the wisdom meaning is open to interpretation, and can also mean intellect, knowledge or reason, resourcefulness, or wit.

智 is also one of the five tenets of Confucius.

智 is sometimes included in the Bushido code but is usually not considered part of the seven key concepts of the code.

See our Wisdom in Chinese, Japanese and Korean page for more wisdom-related calligraphy.

See Also: Learn From Wisdom | Confucius

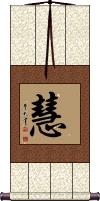

Wisdom

(All-Knowing)

Beyond wisdom, 智慧 can be translated as knowledge, sagacity, sense, and intelligence.

The first character means “wise” or “smart,” and the second character means “intelligence.”

Note: 智慧 is used commonly in Chinese and is a less-common word in Japanese and Korean. If your audience is Japanese, I suggest our other Japanese wisdom option.

This means intellect or wisdom in Japanese too but is a more unusual way to write this word (though both versions are pronounced the same in Japanese).

See Also: Learn From Wisdom

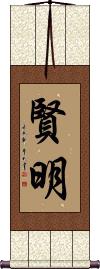

Wisdom / Intelligence

Wisdom / Intelligence

賢明 is a Japanese word that refers to wisdom, intelligence, and prudence.

賢明 was originally a Chinese word that referred to a wise person or enlightened ruler. It means wise and able, sagacious now in China.

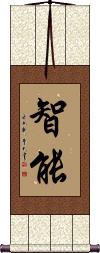

Intelligence / Intellect

These two characters mean intelligence or intelligent.

The first character means wisdom, intellect, or knowledge.

The second means ability, talent, skill, capacity, capable, able, and can even mean competent.

Together, 知能 can mean “capacity for wisdom,” “useful knowledge,” or even “mental power.” Obviously, this translates more clearly into English as “intelligence.”

Note: This is not the same word used to mean “military intelligence.” See our other entry for that.

![]() In modern Japan, they tend to use a version of the first character without the bottom radical. If your audience for this artwork is Japanese, please click on the Kanji to the right instead of the button above.

In modern Japan, they tend to use a version of the first character without the bottom radical. If your audience for this artwork is Japanese, please click on the Kanji to the right instead of the button above.

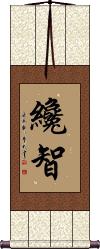

Wisdom / Intelligence

Wisdom / Brilliance

In Chinese, 纔智 means “ability and wisdom” or “ability and intelligence.”

纔智 can also be defined as brilliance or genius.

In Japanese, 纔智 takes on a meaning more of “wit and intelligence.”

![]() Note that the ancient/traditional form is shown above. After WWII, in both Japan and China, the first character was simplified. If you want this reformed/simplified version, just click on the characters to the right, instead of the button above. This is a good choice if your audience is Japanese.

Note that the ancient/traditional form is shown above. After WWII, in both Japan and China, the first character was simplified. If you want this reformed/simplified version, just click on the characters to the right, instead of the button above. This is a good choice if your audience is Japanese.

When Three People Gather, Wisdom is Multiplied

三人寄れば文殊の知恵 literally means “when three people meet, wisdom is exchanged.”

Some will suggest this means when three people come together, their wisdom is multiplied.

That wisdom part can also be translated as wit, sagacity, intelligence, or Buddhist Prajna (insight leading to enlightenment).

In the middle of this proverb is “monju,” suggesting “transcendent wisdom.” This is where the multiplication of wisdom ideas comes from.

Note: This is very similar to the Chinese proverb, "When 3 people meet, one becomes a teacher."

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

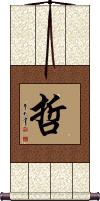

Tetsu / Wise Sage

哲 is a Japanese name that is often romanized as Tetsu.

The meaning of the character can be: philosophy; wise; sage; wise man; philosopher; disciple; sagacity; wisdom; intelligence.

哲 can also be romanized as: Yutaka; Masaru; Hiroshi; Tooru; Tetsuji; Choru; Satoru; Satoshi; Akira; Aki.

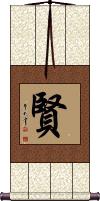

Wise and Virtuous

賢 is used to refer to being a wise, trustworthy, and virtuous person. But it also contains the ideas of intelligence, genius, scholarship, virtue, sage, saint, good, and excellent in character.

賢 is used in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja. Also used in a Buddhist context with the same meaning.

Note: Can also be the male given name, Masaru, in Japanese.

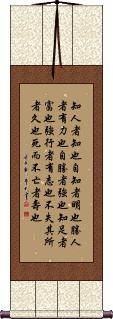

Daodejing / Tao Te Ching - Chapter 33

This is referred to as passage or chapter 33 of the Dao De Jing (often Romanized as “Tao Te Ching”).

These are the words of the philosopher Laozi (Lao Tzu).

To know others is wisdom;

To know oneself is acuity/intelligence.

To conquer others is power,

To conquer oneself is strength.

To know contentment is to have wealth.

To act resolutely is to have purpose.

To stay one's ground is to be enduring.

To die and yet not be forgotten is to be long-lived.

To understand others is to be knowledgeable;

To understand yourself is to be wise.

To conquer others is to have strength;

To conquer yourself is to be strong.

To know when you have enough is to be rich.

To go forward with strength is to have ambition.

To not lose your place is to be long-lasting.

To die but not be forgotten -- that's true long life.

He who is content is rich;

He who acts with persistence has will;

He who does not lose his roots will endure;

He who dies physically but preserves the Dao

will enjoy a long after-life.

Notes:

During our research, the Chinese characters shown here are probably the most accurate to the original text of Laozi. These were taken for the most part from the Mawangdui 1973 and Guodan 1993 manuscripts which pre-date other Daodejing texts by about 1000 years.

Grammar was a little different in Laozi’s time. So you should consider this to be the ancient Chinese version. Some have modernized this passage by adding, removing, or swapping articles and changing the grammar (we felt the oldest and most original version would be more desirable). You may find other versions printed in books or online - sometimes these modern texts are simply used to explain to Chinese people what the original text really means.

This language issue can be compared in English by thinking how the King James (known as the Authorized version in Great Britain) Bible from 1611 was written, and comparing it to modern English. Now imagine that the Daodejing was probably written around 403 BCE (2000 years before the King James Version of the Bible). To a Chinese person, the original Daodejing reads like text that is 3 times more detached compared to Shakespeare’s English is to our modern-day speech.

Extended notes:

While on this Biblical text comparison, it should be noted, that just like the Bible, all the original texts of the Daodejing were lost or destroyed long ago. Just as with the scripture used to create the Bible, various manuscripts exist, many with variations or copyist errors. Just as the earliest New Testament scripture (incomplete) is from 170 years after Christ, the earliest Daodejing manuscript (incomplete) is from 100-200 years after the death of Laozi.

The reason that the originals were lost probably has a lot to do with the first Qin Emperor. Upon taking power and unifying China, he ordered the burning and destruction of all books (scrolls/rolls) except those pertaining to Chinese medicine and a few other subjects. The surviving Daodejing manuscripts were either hidden on purpose or simply forgotten about. Some were not unearthed until as late as 1993.

We compared a lot of research by various archeologists and historians before deciding on this as the most accurate and correct version. But one must allow that it may not be perfect, or the actual and original as from the hand of Laozi himself.

Fatal error: Cannot redeclare foreignPrice() (previously declared in /home/gwest/web/chinesescrollpainting.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php:22) in /home/gwest/web/orientaloutpost.com/public_html/includes/currencyconverter.php on line 22